Much of the work in the field of Basic Writing has primarily focused on identity, pedagogy, and justification, but not necessarily in that particular order. After this course, I certainly envision my research contributing to the field most likely in more than one of these areas, yet I would be remiss not to acknowledge the weight of importance this responsibility carries. I cannot just throw on the “scholar” title like a name tag at a social event; being a scholar is an identity recognized by the body of work I put forth. Over the course of this semester, I have—forgive the cliché—merely scratched the surface of what Basic Writing entails. “Scratch” represents more of the necessity of depth for future research, but it also implies more scope and area covered in regards to the current scholarship within the field. Therefore, even though this paper details much of what I have learned and discussed in one semester, it should be received as a much broader approach to the field with the intention of more focused studies over the course of the Ph.D. program.

Historically, Basic Writing’s genesis, in the opinion of many, would most likely exist with Mina Shaughnessy’s Errors and Expectations where she coined the term “Basic Writer” (1977), yet as Ritter (2008) pointed out, the existence of Basic Writers was much earlier than this, even as early as the inception of Harvard’s FYC. Shaughnessy did present a more official title for this group, but like most discoveries, they often existed before being identified or noticed. And while Ritter (2008) made a strong argument for Basic Writers at the turn of the century and thus rejecting the common socialized view of Basic Writers (Shaughnessy, 1977), I argue that they easily existed before then. It was not until the turn of the century that we had more documentation of specific assistance afforded to them as noted by Ritter (2008) whereas before they may have been denied opportunity completely due to perceived inability.

Unfortunately, the exigencies that made Basic Writers visible and known are currently causing Basic Writing to disappear from the four year institutions. Near the turn of the century, Harvard opened its admissions to public high school graduates instead of just the traditional private school sector, allowing for increased student population and, consequently, the need to bridge their high school experience with the university curriculum through FYC. More students meant more variance in their academic abilities with some falling below the standards set in place and the subsequent need for additional instruction. However, as the standards of admission continued to grow over the next one hundred years, the university’s desire to preserve certain academic standards did also. Basic Writing, in the latter part of the twentieth century and even now, became a sign of “eroding standards” and began to be pushed to community college settings, essentially called “mainstreaming.” This is where I feel my contributions to the field begin to materialize in my mind. I understand that my scholarship is more than just advancing the field in general, it is advancing it by preserving it, justifying its existence and the need for further understanding as to who a Basic Writer is and what his or her path is in higher education.

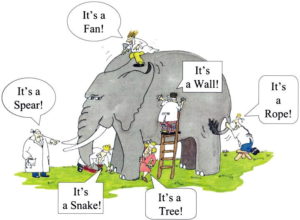

Part of accomplishing this is finding the right approach to establish the need for Basic Writing. I was not exactly sure what this would be at first, but the more I thought about who Basic Writers are, the more I realized their definition is localized as others have noted (Adler-Kassner and Harrington, 2012, p. 30). But even with this variable from institution to institution, a common thread is that each student still retains literacies in other parts of his or her life, which led me to transfer theory. A hot topic in composition studies but certainly not new, transfer focuses on literacies a student may already have and how this might contribute to improving literacies in a different context. This could be from discipline to discipline, a lower to higher grade level, or even from informal to academic context. FYC often looks to the discipline to discipline transfer and K-12 to the vertical transfer, but I have found great value in the informal (external) to academic (internal) context simply because Basic Writers traditionally struggle in the academic context in general, not just in the composition classroom. They have trouble navigating the university and understanding the discourse present there (Bartholomae, 1986; Hindman, 1993; Pozorski, 2013), yet difficulties in one context does not insinuate struggles in all. Basic Writers often have literacies in other areas, which fosters the idea of using success in one area to help in another. This “boundary-crossing” is a “[b]ringing [of] ideas, concepts, or instruments from one domain into another, apparently unrelated one. . .” (Donahue, 2012, p. 165). Theoretically, transfer makes sense for Basic Writing research, but this is still not enough to justify it.

The predominant currency in academia is research and statistics, those that show the overall importance and success of a program or a course in connection with the mission of the university. The theoretical is fine, but when much of the discussion is only that, we must understand its limits and that “[it is] hollow—we might even say ‘empty rhetoric’ unless [it is] supported by data” (Adler-Kassner & Harrington, 2006, p.43). We must apply the theoretical and establish results, but much of the discussion of transfer has been focused on qualitative data such as interviews, case studies, and personal accounts (Anson, 2016; Clay-Buck & Tuberville, 2015; Vie, 2015). Through grounded theory, I could use qualitative data to establish a framework for quantitative data later. Can I do all of this in a single Ph.D. program? Most likely no, but this post is about where I position my studies in the field, and all of it certainly does not have to happen now.

Ideally, the Objects of Study I would like to examine would be the expected student writing taking place in the classroom (drafts, prewriting, CMC) in addition to “short-form digital writing” (Pigg, Grabill, Brunk-Chavez, Moore, Rosinski & Curran, 2014, p. 108) taking place in external contexts such as social media sites or even text messaging. Granted this is fairly broad, but it is a start. The more I have thought about this over the course of the semester and even before I began my studies in the Ph.D. program, I have realized that students enjoy sharing their opinions on current issues and topics that garner their interest, yet they often do not consider the complexities of what and how they are communicating.

The “how” is where I feel transfer in Basic Writing might be most

applicable since the curriculum often focuses on improving writing from sentence to paragraph, paragraph to essay. Apart from the expected misspellings and slang in social media posts, how are students writing these posts on a sentence level? How many are declarative statements? How many are complex or compound sentences? And do the thoughts they are joining warrant such a structure? Most likely, students are not thinking about the connection of form and content here, which parallels their lack of concern for it in the classroom. If they lack in both areas, what is transferable? To begin, it is their care for and approach to it. Communicating well in academics is for a grade, but writing well in social media is for a specific purpose or effect, usually not a grade. Also, if they depend on declarative statements so often on social media, does this contribute and explain choppy writing in essays? Do these students have an awareness of audience in either context? Do they feel their writing in the social media context is accomplishing something? I have a few questions running through my head, but my hope is that the answer to one of these might lead to a better understanding of Basic Writing and the Basic Writer.

Being a scholar of Basic Writing is not any more valuable than being a scholar in another area, but the context of this work might have more immediate relevance in the justification and stability of Basic Writing compared to others. Reducing Basic Writers to simply those who need more assistance due to inability and/or traditionally poor instruction in the K-12 setting perpetuates marginalization of an often far more complex and misunderstood group of students. The axiological concerns are vested in not just preventing the ouster of Basic Writing from the university setting, but it is embedded in the idea that stabilizing the importance of this subject might provide some of the same for the larger field of composition. It also gives more identity for and understanding of a group of students needing more than just a little assistance before FYC. They just need their voice heard, and I believe my studies into how we can make them aware of their voice outside academia can transfer to an awareness within it.

References

Adler-Kassner, L., & Harrington, S. (2006). In the Here and Now: Public Policy and Basic Writing. Journal Of Basic Writing (CUNY), 25(2), 27-48. Retrieved from http://www.asu.edu/clas/english/composition/cbw/jbw.html

Adler-Kassner, L., & Harrington, S. (2012). Creation Myths and Flash Points: Understanding Basic Writing through Conflicted Stories. In K. Ritter & P. Kei Matsuda (Eds.), Exploring Composition Studies (pp. 13-35). Boulder, CO: UP of Colorado.

Anson, C. M. (2016). The Pop Warner Chronicles: A Case Study in Contextual Adaptation and the Transfer of Writing Ability. College Composition and Communication, 67(4), 518-549. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.liberty.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.liberty.edu/docview/1798722905?accountid=12085

Bartholomae, D. (1986). INVENTING THE UNIVERSITY. Journal of Basic Writing, 5(1), 4-23. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43443456

Clay-Buck, H., & Tuberville, B. (2015). Going off the grid: Re-examining technology in the basic writing classroom. Research & Teaching in Developmental Education, 31(2), 20-25. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.liberty.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.liberty.edu/docview/1684790445?accountid=12085

Donahue, C. (2012). Transfer, Portability, Generalization: (How) Does Composition Expertise “Carry”?. In K. Ritter & P. Kei Matsuda (Eds.), Exploring Composition Studies (pp. 145-166). Boulder, CO: UP of Colorado.

Hindman, J. (1993). REINVENTING THE UNIVERSITY: FINDING THE PLACE FOR BASIC WRITERS. Journal of Basic Writing, 12(2), 55-76. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43443613

Pigg, S., Grabill, J. T., Brunk-Chavez, B., Moore, J. L., Rosinski, P., & Curran, P. G. (2014). Ubiquitous writing, technologies, and the social practice of literacies of coordination. Written Communication, 31(1), 91-117. doi: 10.1177/0741088313514023

Pozorski, A. (2013). Podcast paralysis: Inventing the university in the twenty-first century. Writing & Pedagogy, 5(2), 189.

Ritter, K. (2008). Before Mina Shaughnessy: Basic Writing at Yale, 1920-1960. College Composition And Communication, 60(1), 12-45. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20457043

Shaughnessy, M. (1977). Errors and Expectations: A Guide for the Teacher of Basic Writing. New York: Oxford UP.

Vie, S. (2015). What’s going on?: Challenges and opportunities for social media use in the writing classroom. The Journal of Faculty Development, 29(2), 33-44. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.liberty.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.liberty.edu/docview/1776597451?accountid=12085