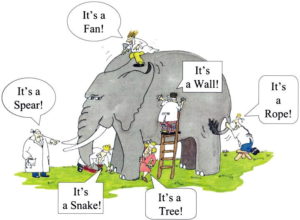

Much of the discussion about transfer focuses on beginning writers working to improve, especially in the academic setting. For example, we might examine transfer as it pertains to a FYC student, her writing skills developed in informal situations such as social media, and how awareness of audience there might help her develop awareness of audience in the academic setting. Anson (2016), on the other hand, documented a different perspective of transfer as evidenced by Martin, a college professor, and his struggle to write a weekly recap of his son’s Pop Warner football games. While his writing for work was often highly successful in multiple genres and modes, which exemplified his ability to write well in various situations and often at the highest levels of academics, the new task of writing a simple review posed a significant challenge. Anson (2016) stated, “Clearly, Martin’s summaries demonstrated a high level of writing competence independent of their context: the resources of a sophisticated vocabulary, expert control of syntax, a penchant for smart phrasing, organizational skills, rhetorical savvy, impeccable grammar. But in this context, such ability was beside the point: writing is deemed successful by the standards of a particular community of practice or group of readers” (p.531). The definition of “writing expertise” is localized to particular discourses, and Martin struggled with a far more simplistic discourse than he was accustomed. Using Beaufort’s (2007) framework of writing expertise, Anson (2016) breaks down Martin’s “expertise” in five areas and discussed where it did or did not overlap in the unfamiliar context, essentially explaining why he struggled to transfer his prior skills and knowledge to a rather simple task.

While Anson’s (2016) study does not focus on Basic or first-year writers, which will probably be who I choose to follow in my research, I found his article to be quite informative of how transfer is not necessarily difficult because of the novice status of writers. Any writer can feel comfortable and entrenched in a certain discourse, no matter their awareness of the rhetorical situation or their writing abilities. I have noticed the trend for researchers to focus on transfer at the introductory level, largely because the students are learning something new, but understanding the struggle to be more universal and less limited gives more insight to where transfer can and does exist.

The primary difficulty in Martin’s case was the community of practice, not his ability to write, which is true for many. Anson (2016) commented that there is increasing “scholarship [looking] to explore how writers conceptualize transient, overlapping, unstable communities. And it is just starting to account for the degree of unity and fragmentation within such communities and the extent to which their actors are situated within multiply configured spaces, each with its own shared assumptions and knowledge. (p. 537). I have often perceived the academic classroom as a more stable environment with clear expectations laid out for student writing; however, perhaps I should revisit this view. Is the classroom environment stable with familiar and easy to read structures, especially as the students bring knowledge of K-12 academic settings to the university atmosphere? Or is there a degree of negative transfer that occurs because the students perceive the community of practice to be more unstable?

This case study not only examines transfer, but it provides me with some ideas of more OoSes I might use. In addition, the perception of why students struggle with transfer is more about context than what might have been apparent before.

References

Anson, C. M. (2016). The Pop Warner Chronicles: A Case Study in Contextual Adaptation and the Transfer of Writing Ability. College Composition and Communication, 67(4), 518-549. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.liberty.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.liberty.edu/docview/1798722905?accountid=12085

Beaufort, Anne. (2007). College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Logan: Utah State UP.