Aligning with a certain position, essentially choosing sides, is not difficult to do: I root for the Boston Red Sox (i.e. my side). Yet, when considering the implications of identifying my epistemological alignment, I am hesitant, though paralyzed would probably be a better word. It is not as easy as merely choosing a side, picking a team to root for, or buying memorabilia and becoming a part of the crowd watching the game. In academia, such a choice does not create a passive existence in the stands, merely there to watch the spectacle that is scholarship; this choice is my identification with a particular view with specific people and identified values, and it is a marker of not only who I am as a person, but also who I am as a pedagogue and a scholar. So essentially, this paper is about identifying an essential part of who I am.

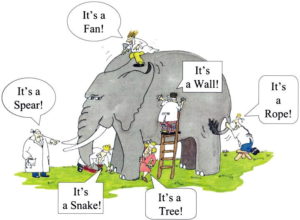

With this question of identity in mind, I thought about the studies I am most drawn to, and the principles that those studies emanate from, which was social constructivism, recognizing how we create knowledge socially. To be clear, I do believe in absolute knowledge though some social constructivists would cringe at the term, but I perceive this as only partially revealed at times, obstructed by the complexities of political,

social, and cultural factors. The knowledge that is socially constructed, one that changes as the external factors change and what constructivists consider “new knowledge” is a different view or understanding of the absolute knowledge we thirst for. Essentially, it is not necessarily “new,” but it is new to us. It exists beyond our measure or complete understanding at any one point in time; however, the parts revealed through scholarship are accessible and allow us to piece together the absolute knowledge we seek.

Social constructivism allows for a thorough analytical approach to the complex situations created in classes. Joe Kincheloe (2006) criticized the reductionist approaches that exist in the K-12 setting, which uses standardized testing models that limit knowledge to a package moving from theorists to educators to students; he argued for more reciprocity between educators and researchers in an effort to recognize the political, social, and cultural factors at play in the classroom. Leigh Jonaitis (2012) discussed the importance of recognizing Computer Mediated Technologies in the classroom through a transactional view, essentially seeing the interconnectivity of Basic Writers and CMT: “Consideration of technology in the basic writing classroom, then, is not a luxury, but instead a crucial part of considering the constantly evolving literacy practices that are such a large part of basic writers’ lives” (p.51). Both Kincheloe (2006) and Jonaitis (2012) suggested that approaching any of these components as though they are autonomous would be counterproductive to pedagogical practices and understanding what is actually occurring in the classroom; thus, their constructivist approaches are informing their views of pedagogy.

Limiting any component—human, technological, geographical—in this equation without recognizing the complexities would hinder the “educational growth” Dewey (1916) defined in his literature. Also, without recognizing the political implications of our own institutional practices and structures such as classifying Basic Writers, we create scenarios where students struggle to navigate the university, an unfamiliar terrain and discourse for them (Bartholomae, 1986; Hindman, 1993; Pozorski, 2013). The university, the faculty member, the students, and the technology all merge in a classroom setting, creating a situation where scholars must recognize not only the complexity this produces, but how those individual factors influence each other.

My earlier post (Paper #2) highlights the question of transfer in the university setting, especially with Basic Writers, which leads me to possible Objects of Study being student writing and technology (i.e. social media). I have considered examining student communication on Twitter and how they navigate the rhetorical situations existing there and if this same practice occurs in the classroom, an academic setting. Are students constructing knowledge in the classroom as different from the knowledge on Twitter? Why or why not? What factors—social, cultural, political—creates the rift between their writing in two settings and how could literacies from one successfully transfer to the other. Pozorski (2013) suggested that the incorporation of common and familiar technologies for students into the classroom would create more confusion and resistance because the academic setting influenced student perception of podcasts. While this is one particular study, I think more research is necessary.

In establishing an epistemological alignment, I am establishing a key foundation for future scholarship and pedagogical theories. To be blunt, this choice is incredibly important; however, it is not limiting. Richard Fulkerson (1990) stated, “Axiological commitments set up goals for pedagogy, but do not prescribe how best to reach them, and one’s decision about how to reach the goal will be guided but not determined by views of writing as a process, just as both procedural and pedagogical theories will be based on whatever research or experience one’s epistemology allows to constitute knowledge” (p.418). Fulkerson’s statement reveals just how epistemology serves as a core component of my profession and future studies, informing my practices as a teacher and later leading to the results I value as a result of my practices. I feel that a social constructivist approach is best when approaching the objects of study previously mentioned. It creates a focused view on the individual components while also recognizing the complexities resulting from their interaction. And while I may share this view with others, my pedagogical philosophies and axiological considerations will still create disparities, those which are common in the discourse of the field in the pursuit of knowledge.

References

Bartholomae, D. (1986). INVENTING THE UNIVERSITY. Journal of Basic Writing, 5(1), 4-23. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43443456

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. New York: Macmillan.

Fulkerson, R. (1990). Composition Theory in the Eighties: Axiological Consensus and Paradigmatic Diversity. College Composition and Communication, 41(4), 409-429. doi:1. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/357931

Hindman, J. (1993). REINVENTING THE UNIVERSITY: FINDING THE PLACE FOR BASIC WRITERS. Journal of Basic Writing, 12(2), 55-76. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43443613

Jonaitis, L. (2012). Troubling Discourse: Basic Writing and Computer-Mediated Technologies. Journal of Basic Writing, 31(1), 36-58. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43741085

Kincheloe, J. (2011). A Critical Complex Epistemology of Practice. Counterpoints, 352, 219-230. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/42980820

Pozorski, A. (2013). Podcast paralysis: Inventing the university in the twenty-first century. Writing & Pedagogy, 5(2), 189.